CHILE HAS ABOUT 795 DEPOSITS, MANY ABANDONED AND WITHOUT EFFECTIVE REGULATION: Project seeks to recover cobalt and nickel from mine tailings.

October 27, 2025

The initiative, developed by Adolfo Ibáñez University, with the support of Antofagasta Minerals and KeyProcess, seeks to transform deposits into a new source of strategic metals.

From waste to leading the energy transition. This is the goal of the BioElectroTor project, led by Adolfo Ibáñez University, with support from KeyProcess and Antofagasta Minerals (AMSA). It is a bioelectrochemical reactor that uses bacteria and polarized electrodes to extract cobalt and nickel from tailings with less energy, reducing the environmental impact and positioning itself as a promising option for the remining of these metals, which places it above other traditional methods such as bioleaching or hydrometallurgy.

The proposal also opens the possibility of converting a historical environmental liability into a competitive advantage for Chilean mining, according to Javiera Toledo, a researcher at Adolfo Ibáñez University and leader of the project.

“A major challenge is that each tailings dam has a different composition, and this can affect the efficiency of the process. That’s why we developed modular reactors capable of adapting to varying conditions, with the goal of making the technology scalable and sustainable over time,” she says.

THE BUSINESS VISION

For an innovation like BioElectroTor to transcend the laboratory, it is key to have the industry’s perspective. This is the role of KeyProcess, a Chilean company participating as a technology partner, contributing its experience in process engineering and integration with real-life operations.

For Marcela Paz Bastias, KeyProcess’s Technology Director, the challenge lies not only in technical validation, but also in the ability to gradually scale the technology, maintaining biological and electrochemical stability under varying operating conditions and ensuring competitive operating costs. For this reason, the company promotes the development of collaborations between industrial, academic, and public sectors, with the goal of bridging the gap between scientific knowledge and practical application.

“BioElectroTor’s scalability is achievable if approached gradually and with an integrated engineering approach,” notes Bastias. She adds that, “at the pilot level, the challenge lies in controlling biological and electrochemical stability; and at the industrial level, in integrating the system into existing processes and optimizing costs. We believe that synergies between key players can make this technology viable and open a new standard for tailings treatment and recovery.”

The pilot project is supported by Antofagasta Minerals, which provided real tailings samples to validate the operation of the BioElectroTor under conditions representative of Chilean industry.

This collaboration not only allows the technology to be tested with specific materials but also paves the way for its future implementation at real-world sites. In a scenario of growing global demand for cobalt and nickel, critical minerals for electromobility and energy storage, Chile could add a new source of value to its production portfolio, diversifying its role beyond copper and lithium, according to Toledo.

“Thanks to the collaboration with AMSA, at the end of the project we will be able to count on experimental validation in a representative environment, which strengthens the projection of this technology into future stages of application,” he notes.

PENDING REGULATION

Tailings reprocessing to recover critical minerals cannot become a real solution as long as the regulatory gap regarding abandoned deposits persists, according to Raimundo Gómez, director of Fundación Relaves.

Today, the Mine Closure Law only applies from 2012 onward, leaving hundreds of previous liabilities unregulated. Without a legal framework that defines responsibilities, intervention standards, and governance mechanisms, these deposits will continue to drift, generating risks for communities and discouraging investment in innovative technologies. Furthermore, economic incentives and public policies that actively promote remining are required, transforming a historical problem into a strategic opportunity.

“There must be regulations regarding what to do with abandoned tailings, how to pursue public-private responsibility, and, once this situation is regulated, generate economic incentives so that companies actually want to work on them,” adds Gómez. According to the specialist, “abandoned tailings sometimes have higher ore grades than the rock itself; in other words, yes, it would be a good way to work on them, but with adequate incentives so that companies actually want to intervene.”

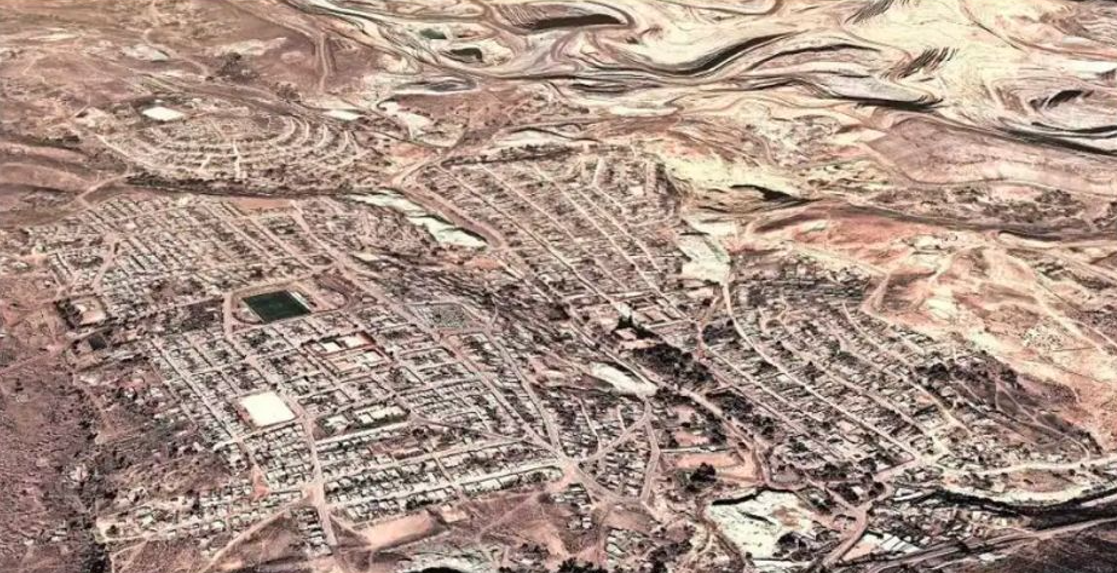

THE TAILINGS DEBT

Chile faces a historic challenge with approximately 795 tailings dams, many of them abandoned and without effective regulation, according to the National Geology and Mining Service. These mining liabilities represent a latent risk to communities and ecosystems, including the infiltration of heavy metals into underground water, the dispersion of particulate matter by wind, and even the risk of collapse in urban and rural areas.

Cases such as the collapse of the tailings dam in Las Palmas following the 2010 earthquake, which claimed the lives of an entire family, reveal the urgency of comprehensively addressing a problem that combines environmental, social, and health debt, says Raimundo Gómez of the Relaves Foundation.

“In Chile, there is no law that addresses the hundreds of abandoned tailings dumps we have. Many are located in cities, on riverbanks, or in watersheds, polluting water and affecting people’s health. It’s a historical debt comparable to the lack of a soil standard that defines when land is contaminated and when it isn’t,” warns Gómez. In addition to the immediate environmental risks, the lack of an updated land registry makes it difficult to accurately assess the magnitude of the problem.

This not only aggravates the exposure of entire communities to contaminated dust and water, but also delays solutions that could turn some of these liabilities into assets, considering that many tailings retain higher metal concentrations than fresh rock. “There must be a reliable land registry with up-to-date information, and this isn’t currently the case. We see that the land registry lacks records of tailings.

For example, the Arica Region is considered a tailings dam, and there are more than six in the city. Many are located in the same cities, such as Andacollo or Copiapó, on riverbanks or in basins, polluting the water and reaching people’s homes,” he concludes.